It was Halloween. Almost a year had passed. Hard to believe.

It was Halloween. Almost a year had passed. Hard to believe.

As soon as the foot traffic cleared, Daren pointed the umbrella toward the road and pulled its runner down to close it, but hadn’t perfectly aligned the faded parts, which left some of the red canvas exposed. The umbrella had come free with a bottle of perfume. A gift for Sophie. Then Matt was born, and she’d thrown the umbrella in the back of the Subaru, “for emergencies.” Sun had bleached it; plastic was peeling off the handle. When they’d released the contents of the car to him, absurdly, this bent umbrella was what he brought home. Still in shock, still angry and in pain, he’d unthinkingly dropped it into an old stoneware churn by the front door with the hiking sticks—and there it’d stayed.

Matt wouldn’t come near the thing until he’d shaken the spiders out.

“Hold up, Matt,” Daren said from the sidewalk. “Stay out where I can see you. Hear me? Don’t run too far ahead.”

Soph had loved Halloween. What a farce.

Matt’s feet clopped. New shoes that fit would have been a waste of money, useless in a matter of months, Daren figured, and if it fell to him to decide, and it did, then he was going to handle things his way, the sensible way. Those details Sophie used to go on about were his to keep track of now. He wished they weren’t.

She’d had a talent for making light of things. For making things light, if she wanted to.

The air felt crisper after the downpour, cooler. Every aspect of the world at street level had taken on a fresh iridescence, like the shells of certain species of beetle, enhanced by fifty flashlights waved at crossbeams from the ends of too many stub arms. Too early for this, Daren thought, annoyed. Dusk, not dark. But little man Matt looked genuinely upbeat, excited for a change, finally an expression other than that pained squinty grin that worried his teachers, or made them think he was mocking them. Matt had run zigzag around a group of three or four mothers to catch up with a kid he knew from school, Kev something or other. Daren was fully aware he had no clue how to do group outings or parent cliques. He’d liked knowing nothing. What were they supposed to talk about? Kids? Matt was the only kid in the world who interested him. Lumbering behind, Daren ran through points from the faculty meeting earlier as he tapped the umbrella’s tip on the cement, trailing three mothers, perhaps four. One of them didn’t quite fit in.

Sophie had lived for Halloween. She’d called it Samhain and each year used to talk excitedly about it and how it’d morphed into All Hallows Eve, repeating the story like a tired litany every time. “Both mark the beginning of the cold and dark season, a time when fairies and unsettled spirits roam freely,” she’d say. But he’d say that in this era, this supremely unimaginative era that they actually lived in—what, with months and millions spent celebrating it—what exactly were they supposed to celebrate? No, he did not care for Halloween and had told her as much. Maybe he might have cared if he was a peasant afraid of crop failures, or actually believed in a soul or spirits that could fly out of purgatory, or that cakes blessed by priests had the power to console spirits when they did fly out. Better some salt and a little wine, he’d said, with plenty wine to spare. Maybe then he might like it. Don’t forget, she would add, the gifts can also lure a loved one home. But the masks were important, she always said, putting hers on: it was their job to scare off anything else.

Matt’s Batman cape had fallen off him no less than five times already, and as a result Daren had to carry it over his free arm. But from the look of it, Matt’s little neck and shoulders were doing the heavy lifting for the night with that truly huge papier-mâché wolf’s head of Sophie’s. Determined to wear it, Matt bounded up to each of the craftsman style houses holding the mask on with one hand, stepped onto their pumpkin-lit porches, and thrust his Batbag out for candy. Black, orange, and red were the evening’s ordained colors, but above, a turquoise sky offset a line of trim young maples. There was a faintly sweet smell of rotted leaves mixed with Jolly Ranchers; colors bounced back as painted abstractions from puddles and thin runnels that gurgled noisily into drains.

Sophie had handled all this, before.

Three days ago, a woman called; he couldn’t have picked her out of a lineup if he tried. She called and invited him to join her and some others for trick-or-treat. He didn’t know what to say. There was an obvious awkwardness on the line. He said no. Any one of these women could be her, for all he knew. Left to right, the first two wore jeans; three wore rain ponchos; and number three had squeezed into a pair of black yoga pants that stopped just below the knees. All three had armed themselves with compact umbrellas and flashlights, but number two also wielded a glitter boa and star-wand. He probably should have shaved. His stiff brown hair flopped into his eyes, overgrown like a grunge musician from back-in-the-day, or one of those Eastern Bloc refugees who’d toppled a wall—and yet, and yet, he was himself, a man in his mid-thirties who’d taken a position teaching undergraduates while working on his doctoral thesis in anthropology. His second doctoral thesis. The umbrella hung by two fingers as he untucked his starched white shirt and wiped his glasses, careful to avoid the stain from lunch when the chip broke.

The fourth mother trailed just behind and to the right of the other three. She wore a beige dress with canvas shoes—the sort of shoes the young sorority girls in his morning classes wore. White socks, spotless white from the ankles down, nothing like Sophie’s moccasins or her bright gypsy skirts. Not like Sophie at all. The woman’s pale thin calves quivered with each hard step. Her hair flowed long and sleek, shiny black in the fractured light.

These women would have known Sophie. The three talked together and swung their umbrellas like constable batons. Their vibrant fleshy presences spoke of merit ribbons taped to refrigerators, spiral notebooks on kitchen tables with bubble-lettered entries, playdate Saturdays, and the latest Lifetime special, or whatever, the sort of chick flick Sophie used to rope him into watching, always “highly recommended”—by them—but invariably two whole hours he’d wish to get back. He’d complain, as he remembered it. But only after.

He would have done things differently, if he’d known.

“Matt, get off the lawn! Use the walkway!”

Not one of the women turned to see who’d shouted.

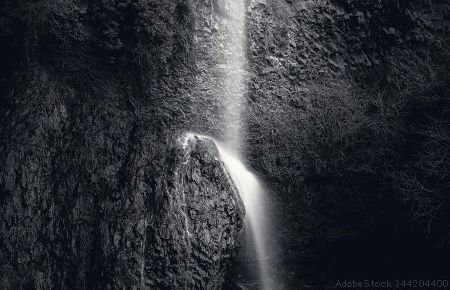

The fourth woman, her hair flowed like a long mournful cry, chthonic, ink black, a lonesome waterfall in some gray underworld abyss, down and across her small back, barely shifting against her skin, and then only the length past her bony shoulder blades where the curve of her spine let it dangle loose in ragged strands. Sophie’s had been soft, short, ash-blond, and curly. Her eyes, as he remembered them, were perpetually round and open, practically never soft or sedate. And she’d had a way of closing her lips around her words, even unspoken ones. What went on in her head, he never really understood. And then she was gone. A year, just about. A mob of strangers at the funeral, and they all said year two would be the worst, told him to brace for it, but call if he needed anything. Yeah, not going to happen. But he and Matt were doing all right, weren’t they? They’d gotten past the worst. Without help. But there were times he wished it’d been him in Sophie’s place—it wasn’t that he wanted to die, he just didn’t want her dead, or to continue on like this in perpetual twilight. Truth was, Sophie might have managed the whole situation better. It might have gone easier for Matt if he’d lost his dad instead.

And what if those believers had it right, that Samhain by some freak miracle of metaphysics had the power to reach Sophie and call her back? After all he and Matt had gone through, it’d be too much. One can’t undo. It wouldn’t be the same. Not the same Sophie.

A crisp wet night, damp yet warm for October. A car turned the corner with high beams on, and its halogens shone directly into his eyes. One of the mothers raised her arm to block it: “Hate those things. What gives them the right?” Daren tried to get a bead on which house Matt had run up to, probably the one with the inflatable mechanical spider, but in the center of his vision there was a negative afterimage, a large purple blotch in a crowd of colorful costumed children. Burned out the photoreceptors. Blinking was no help. Sure enough, everywhere, a pair of purple headlights. Glasses off again, umbrella under his arm, he pressed his eyes with his palm. Glasses back on, he tried blinking more, and his lashes bumped against his bangs.

Great, now streaks—must’ve smudged the lenses. Daren wiped again with his shirt, but no improvement. Maybe his eyes were overcompensating. Or was it phosphenes, from rubbing his eyes? Wisps, not streaks—delicate, gauzy—swooped down in a fifty-degree angle toward the sidewalk, although they seemed to vector from different starting positions. Hard to say, but then they kept whipping to the side, shooting off in new directions, like beams of light reflected off water or glass. An illusion, a trompe-l’oeil, Sophie would have said, though incorrectly. And yet, the black-haired woman kept turning toward the wisps whenever they darted in. Only then did he see the woman’s face, just the edge of it.

The sidewalk was wide. During the next break in traffic, he decided to move up the left side and get a better view of number four.

Couldn’t. The woman with the black hair never turned her head far enough. But he walked too close to the first of the three and stepped on her heel.

“Excuse you,” she said, and glared at him with small eyes, hard, as if deciding whether to smack him. A good bet she had a whistle in that poncho. He really should have shaved. Number-one slipped her shoe back on, grabbing onto number-two—which stopped the others. Him, too. She gave Daren a once-over, guardedly, perhaps imagining they’d met at a PTA meetup. He’d never gone to one. By the next second, and with a sour expression that didn’t do her any favors, she turned and whispered to the other two, and prompted a round of terse nods.

Daren fell back to his former position. He spotted Matt at the upcoming house.

The bat on Matt’s orange plastic bag bulged. Mac-and-cheese didn’t have a prayer of competing with that. But just let him do it, he thought, let him live a little. If the boy gets a stomachache, he’ll recover.

But Daren had a headache. The wisps kept swooping in, long after the purple splotches had gone. He should ask Matt for a piece of candy.

“Yo, Matt!” He waved at the boy. “Come over here a sec, bud.”

But Matt was already midway up the front walk, standing in place while other children shuffled around him. The boy he’d joined, a green skeleton, was tugging on Matt’s bag, and their two arms sawed back and forth until the straps broke. The boy punched Matt in the stomach. Matt bent double, and his wolf mask tumbled off, which made his hair stick up. From where he stood, Daren saw Matt’s little red mouth widen—saw it long before the wail—while the other boy looked up and around him, no way to read his expression under the skull mask, but clearly, he wanted his mother. Of course, the one in the yoga pants. She hurried ahead, cutting through a yard, panting: “Right now, mister! No sir, we do not hit!”

Daren walked up to his son. Matt hadn’t moved. The peculiar wisps seemed to have gathered around them, enough for Daren to check whether they stood under fake cobwebs. But no, and none of the yard’s bushes or branches even came close. Matt gripped the bottom of the papier-mâché wolf mask in his small fist, quiet now, cheeks moist. The orange bag lay on the grass in front of him, its contents dumped into the mud. Daren squatted down, set the umbrella down. Matt simply stared at the ripped bag, grinning in his weird hurt way.

A wisp fluttered in the air between them. The storms were over; all was still, and yet at that same moment, a lock of Matt’s hair shifted across his brow, as if tugged by an unseen hand. Then, as if repelled, the wisp snapped away, like a flagellate in pond water under a microscope. In the grass, next to the bag, there appeared a pair of white shoes, white socks, and above a pair of thin legs, the hem of a beige dress. Why was this woman inserting herself? Daren threw back his head to get a good look at her, but a flashlight’s beam glinted off the scratches in his lenses—he caught only the dark hair and something pale in the middle of it. Behind him, a pair of pink princesses had been shoving each other down the walk; one stumbled onto Daren’s back and tipped him over onto his hands and knees. By the time he righted himself, the woman was gone.

***

Halloween ended on the living room couch. Matt had fallen asleep to The Wizard of Oz. Sometime after one, Daren lifted the limp boy over his shoulder and carried him upstairs to bed. Empty, the wolf’s head kept guard now at the foot of the bed on Matt’s Superman comforter. In the soft glow of streetlamps, Daren laid his son down, his small mouth a blotter of chocolate smears.

In his own darkened bedroom, Daren unbuttoned his shirt and tossed it onto the rocking chair on top of a pile of dirty laundry and the forgotten red umbrella. He unbelted and dropped his corduroy pants to the floor—loose, now, at least two sizes too large. Naked and alone, he crawled into the shadowy crumpled sheets.

Sometime later, a sound woke him, like a fire engine siren, stunningly loud in the cramped space—he looked up, then bolted up, in the grips of a cold sweat. He fumbled for his glasses, heart booming in his chest. At the open window, in the northwest corner of the house, stood the thin woman from earlier. How did she get in? But then he saw, and shuddered.

Her black straight hair lifted in a breeze. Her dull beige dress tipped behind her like a bell. She was leaning out the window while hundreds of white wisps, gossamer yet phosphorescent, flew at her face into flat, empty eye sockets.

Like a sentinel waterspout on some grim medieval cathedral, the woman’s cheekbones protruded grotesquely, sharp and bulbous—her chin jutted a good four inches. And then it hit him: it was some kind of cosmic inversion! Oh, God, Soph, no. Not like this… not for me. Awash in his powerlessness, a loss on top of loss, he felt his heart implode.

It was her.

But it wasn’t. Tears spilled down his face. At the edge of his bed, he gripped the sheets. His breath failed him. The wisps, they couldn’t save themselves any more than he could have from Soph, who’d once stayed and now was gone. They were so drawn to her—this time unable to slip past her or fly away, the fine wisps dove straight into those flat, soulless sockets, and flew out again, out of the revenant’s open mouth, as if thrown back into the ether, discarded, like undigested fish, altered—screaming—in a vicious chromatic spew, a constant prismatic beam!

Pingback: The Ordered Chaos of “Odd Wheels” — and Novels! – Dawn Trowell Jones